Regarding Aid: The Photographic Situation of Humanitarianism

Mekele. ICRC Feeding center. Displaced children. by Catherine Peduzzi, 1984, ICRC, V-P-ET-N-00030-17

In this dissertation I take a cultural history approach that enables an exploration of the way in which photography, mobilized by a range of humanitarian actors, introduced new forms of humanitarianism, expanded the terms of who could be subjects of humanitarian action, and how those distinctions differed or conformed with dominant concepts of humanity at various points in time. An historical approach involves thinking about the ways the present is linked to the past, revealing obligations and responsibilities articulated to it. More specifically, I follow Ariella Azoulay in defining photography as “an event” rather than a technology for producing pictures it is a medium that is “subject to a unique form of temporality—it is made up of an infinite series of encounters” (26). Like Azoulay, I look beyond the content of the pictures to locate the greater force of the medium in the arena of actions and actors that extend beyond the picture’s frame or the little black box of the camera.

Over the course of the dissertation, I explore events and relations associated with:

Henry Dunant’s graphic language in A Memory of Solferino;

Lewis Hine’s European photographs in and immediately after the First World War; and,

a photograph of the French army in Rwanda during the 1994 genocide.

My key questions include:

How has humanitarian photography figured in shaping imagination of humanity and in formulating responses to human suffering? How does thinking historically about humanitarian photography change the way moral obligations and social responsibilities towards suffering others in the present are regarded? How can consideration of the photographic encounter impact humanitarian relations and reconfigure conceptions of the victim, perpetrator and benevolent actor?

With these cases, I seek less to find answers to my questions than to consider the insights and opportunities they provide for reconsidering current events from different points of view.

Background and rationale:

Until recently, scholarship on humanitarian photography has been dominated by criticism and moral debates about representing suffering. While this has been the focus since the last quarter of the twentieth century, the past decade has seen a growth in histories of humanitarian photography. This has added historical depth to earlier critiques at the same time as complement a parallel growth in critical histories of humanitarianism writ large. With the approach I take in my dissertation, I build on existing scholarship while also complementing recent shifts towards beneficiaries’ gazes within humanitarian scholarship and reflection.

Theory and methodology:

I take a combined cultural history and visual theory approach to a case study analysis. I have built my approach around “the recognition that the technology of photography is not just operated by people but that it also operates upon them” (Azoulay 2012: 15).

Applying historical thinking to humanitarian photography is a way of restoring links to the past and in this way also restoring obligations forged with those links.

In this dissertation, I deviate from conceptions that treat photography solely as historical, juridical or forensic evidence, or as a rhetorical and propagandist tool. I approach photography as foremost a cultural, social, and political phenomenon, the dimensions of which extend beyond the content or frame of the picture in order to make plain the interrelations and mutual dependencies that form the foundation of the humanitarian impulse.

Visualizing humanitarianism: Henry Dunant’s “lamentable pictures” spark an international movement

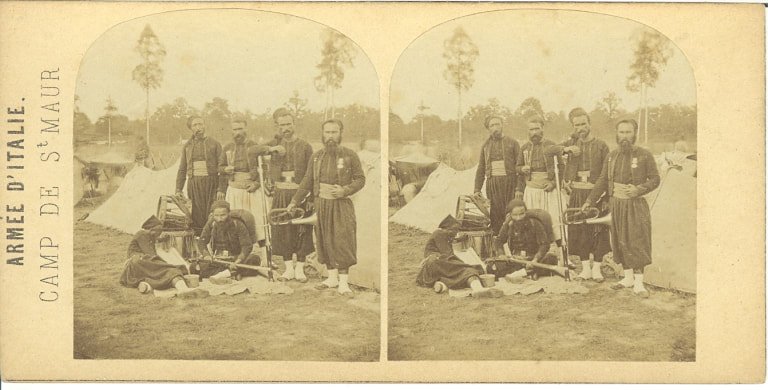

In this chapter, I contend that credit for Dunant’s successes must also go to the popular use of the camera at battles being waged in Europe in that mid-nineteenth century moment. Photography invited new perspectives on the visual world, contributing to a popularization of anti-war sentiments and social democracy ideals. With this case study, I explore ways in which the camera contributed to people being able to see and think differently, reconsidering the dominant heroic discourse of conflict, and apprehending the common soldier as worthy of the same level of care and attention otherwise afforded only to higher ranking citizens. Doing so offers a fresh look at the origins of modern humanitarianism and of humanitarian visual culture. By focusing on suffering without giving name to its sources, he set a tone and example for humanitarian communication that continue to influence humanitarian action—particularly within the ICRC—to this day. The case of Dunant’s “lamentable pictures” is about the role of photography in expanding people’s sentiments, broadening the terms of the “us” worthy of care and attention.

Visual Displacement of Refugees: Lewis Hine’s First World War Photographs for the American Red Cross, 1918-1919

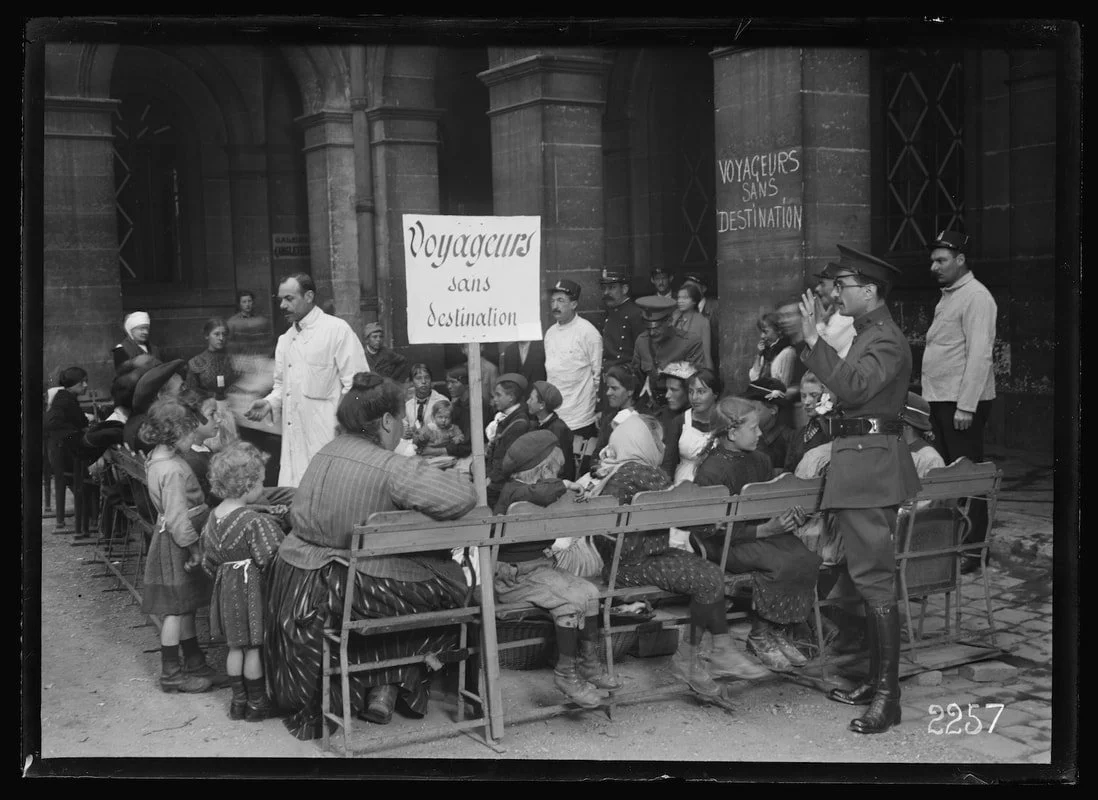

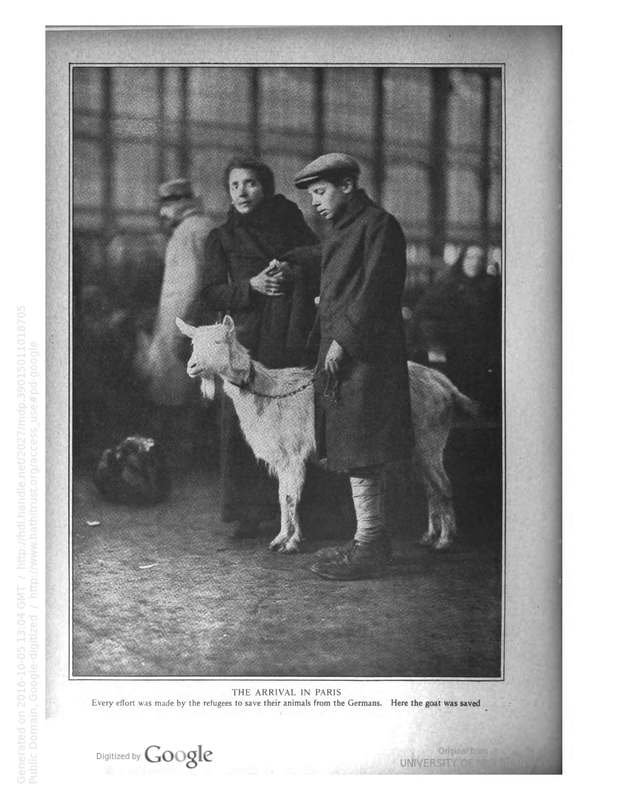

With this case study I focus on the ways in which the ARC framed—and later displaced from the field of view—European refugees. During the war, Hine’s sympathetic pictures of refugees bolstered the ARC to become America’s preeminent civilian war relief agency. After the war, as patriotic humanitarianism was overtaken by nationalistic fervour, the burgeoning humanitarian image of the child displaced pictures of refugees. While helpful in terms of continuing a degree of aid flowing to people who continued to struggle in post-war Europe, the loss of specific attention to refugees proved harmful. Particularly at a time when Eastern European refugees made the transatlantic journey to North America, this visual displacement amplified the hardships of those impacted by territorial displacement. Hine’s extensive photographic collection reveals distinguishing characteristics of refugees that were occluded, resulting in refugees being subject to the same treatment as immigrants.

“Watching” the Rwandan Genocide With a Photograph on a Hillside

This case study proposes an alternative approach to considering photography. The way in which the photograph is placed as the sole photograph on display at the Bisesero genocide memorial site in Rwanda and the way it is mobilized at the site challenges conventional notions of victims, and it enables exploring the perspectives of the different actors (photographers, victims, perpetrators, humanitarian actors) as they converge on the plane of the photograph and that articulate to it as the impact of the picture continues over time. The picture is not a humanitarian photograph in the narrow sense of it being made or used by humanitarian organizations. It is a press photograph made by a British journalist in the final days of the genocide, and it is part of a history in which visual culture proved to be perilous for hundreds of thousands of Rwandans primarily those identified as Tutsi. By tracing the relations within the encounter depicted in the image, and by restoring links between spectators separated by space and time, the photograph reveals the way in which historical thinking of a picture can be a source for building humanitarian sentiment without relying on an appeal to transcendental human essence.

Write a caption for the photo at left

Conclusion

More frequently today, aid organizations are vocalizing their realization that they are no longer the “voice of victims” but rather are at best partners or at the very least interpreters of what is occurring with those on the ground; participating in making the messages (Lyndsay 2015). Recent increased violence against transnational aid organizations has been interpreted as a misunderstanding on the part of would be beneficiaries turned belligerents who supposedly misinterpret the presence of these foreign agencies as a new form of imperialism. Whether this is the case or not, it highlights the importance of history, that impacts of it continue to reverberate in the present.

Photography has great potential to generate sympathy and alter perceptions. It also has potential to restrict vision.

As promising as this is, it is still dependent on “subjective identities, social positioning, political commitments and moral values of its supporters, donors and workers. (Fehrenbach and Rodogno 2016: 1154). In order for humans to recognize each other as “being[s] bound up with others” it is up to those making, using, circulating and discussing photographs to think historically, to restore links to different pasts and to recognize our mutual obligations and interdependencies (Butler 2009: 180).