Creative Practice: Processes

Playful Photographic Practice — Responding to Dark Times

To balance out the difficulties I had to navigate this year (difficulties, I know, that pale in comparison to those faced by so many others), I had the privilege to make time for play. Creativity is a vital human faculty, and one that is essential in solving problems, even 'wicked problems' experienced around the globe, and that we are implicated within in some way or shape. My go-to medium of choice for play-therapy tends to be (nut is not exclusively) photography. This year especially, it was alternative and nineteenth century approaches to photography, and a return for the first time in about 20 years to the darkroom.

Here are some of the outcomes of that fun. More to come.

Digital photograph printed on bamboo paper.

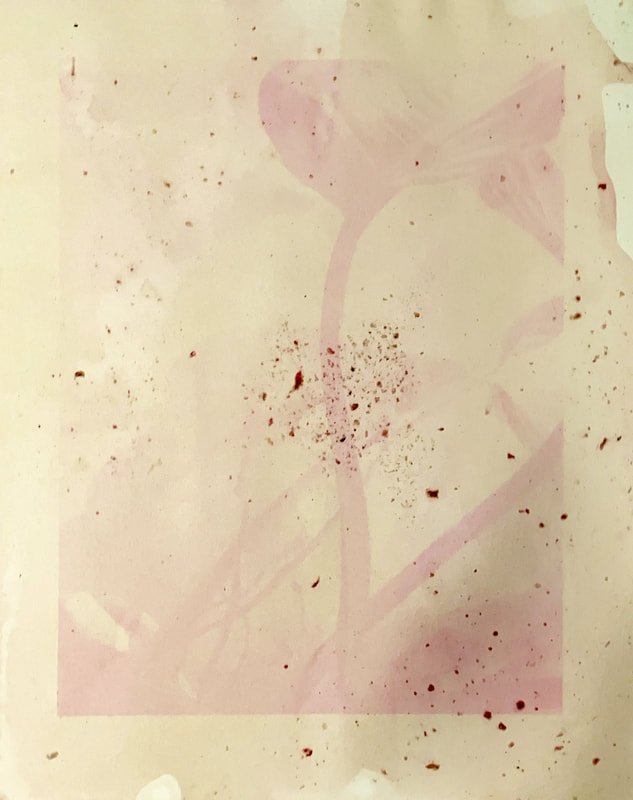

Phylodendron Anthotype (with beet juice).

Digital photograph printed on bamboo paper.

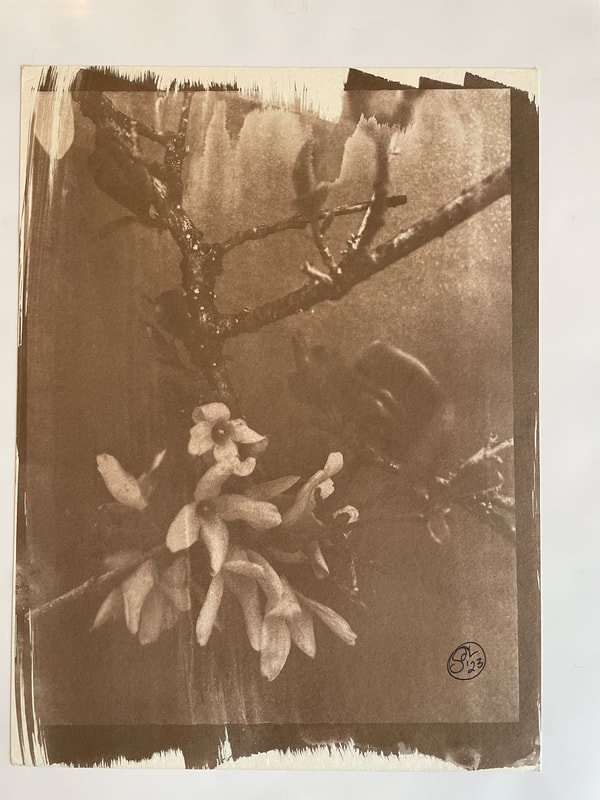

Cyanotype of spring forsythia.

Cyanotype of spring forsythia, toned in green tea.

Digital photograph printed on bamboo paper.

Polaroid 690 — Agave

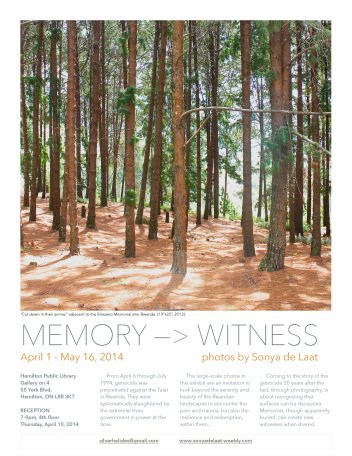

Memory ➔ Witness

Inspired by a survivor of the Rwandan genocide, this photographic exhibition, displayed from April 1 through May 16, 2014 in the Gallery on 4, Hamilton Public Library, Central Branch, is about trauma, memories in the landscape, and creating distant witnesses. The exhibit engages with the spectator, aesthetics, media, humanity and human rights. Entitled Memories ➔ Witness, the exhibit is an example of a photographic practice that attempts to represent unrepresentable suffering while being sensitive to concerns over exploiting pain. It also invites spectators to become witnesses of a past event that has present impact on lived-realities. A witness can be an eyewitness, but can also be anyone who cares to be affected by stories of violence and continues to share these narratives with others.

These images of Rwandan landscapes are meant to ignite the imagination, to direct the mind away from the path of atrocities, especially ethnic, social, racial, or religious one-sided mass killings. As a way of keeping attuned to empathy and goodwill, the spectators’ minds should be haunted by these images just as survivors are haunted by traumatic memories. The bright hues and large scale of the images in this exhibit, facilitate and enhance imaginative abilities. The titles are quotes told to me by survivors, or selected from published testimonies and eyewitness narratives. They add meaning to an otherwise sublime scene, or act as an intrusive thought - jarring the spectator - giving them a sense of the survivors' experience of memory: it is lived, embodied and can be read in landscapes and material that are otherwise apparently benign or idyllic.

"Mille collines, mille colliques... every hill is a bad memory."

"Running blindly we finally reached the marshes."

"Understand this: the genocide will not fade from our minds. Time will hold on to the memories, it will never spare more than a tiny place for the solace of the soul."

"Cut down in their prime"

"Redemption"

"It's a project that's meticulously planned and properly carried out."

"Mille collines, mille colliques...every hill is a bad memory." In making small-talk banter with a survivor about the aesthetic beauty of the Rwandan landscape, his response to me was that each hill represents sadness and horror. Memories , both good and bad, are in the landscapes. The more we scratch beneath the surface of its beauty, the more we can learn about the human condition and our experiences within it.

"I feel at home here." Under these trees, for nearly the full length of time that this area was defended by genocide resistance fighters, survivors from that group camp here to commemorate the nearly 50,000 people who were killed in this area. Many survivors don't know where the remains of their loved ones are, thus places like this, a mass grave site, become familial places of homecoming and comfort.

"I will always tremble whenever I hear voices raised among the leaves of the banana groves". Running and hiding within the different vegetation in the Rwandan landscape was often the only means of survival. Though this image could just as well be used today for tourist brochures or social/environmental campaigns, for survivors of the Rwandan genocide, this image is a reminder of the animalistic existence they endured to save their lives, and how far they have come since then.

"I'm so afraid of meeting my memories...we breathed deeply of death."

"Running blindly, we finally reached the marshes." For nearly a month, she and about 1000 others hid in the wet papyrus marsh pictured behind her. Only about 50 people survived. Though she lost so many loved ones in that time and in the period of instability following the end of the genocide, she is still a matriarch, community leader, farmer and generous human being.

"Redemption." After having watched the murder of his parents, losing other family members, and spending the remainder of the genocide running and hiding from the Interahamwe, this survivor retuned to school, built a home, started a family, and teaches about the genocide. The home is not a symbol of 'moving on' from the past, but is rather about making the present the best in can be in honour of his family members killed in 1994.