Creative Practice: Places

Watch This Space

Photographs fill today’s visual landscape to the point that they appear disposable and relentless.

But photographs do not rush past and bombard in the same way as film and video images.

Photographs allow the eyes to stop, to linger, to watch.

WATCHING photographs means engaging your imagination.

Fill in the action and events that are within and outside the frame.

Focus on a detail, follow it, see where it leads.

Stop at a juxtaposition.

Look beyond, past, through the superficial, the stereotypical, the dominant.

Selfie Stop Kigali, Rwanda, 2015

Downtown Kigali, Rwanda, 2015

Tigo Good Life, Rwanda, 2015

Suburban Kigali, Rwanda, 2015

Locate the photographer’s point of view physically, ideologically, intentionally, actually.

What is the relationship created, perpetuated or missed between the photographer, the subject, the viewer—through the event of the photograph?

Where is the power located?

Are there different degrees of power?

Can it be redistributed depending on how a photograph is used?

Do the elements, details, juxtapositions in the pictures share any similarity to ones in your daily life?

Where do the differences and similarities stem from?

In what way do they disrupt, reinforce, dissolve what you hold to be true?

Africa is not always and all-over violent and dependent.

Contrary to popular imagination there is no deep, dark heart to the continent. Rwanda, where these photographs were made, is in the centre of the continent. It is green, lush and tropical: the land of 1000 hills.

Also contrary to popular misrepresentation, Africa is not a country.

It is a continent.

It has over 50 countries and approximately 3000 languages.

Watching photographs in this way invites the mind—the imagination made up of personal experience, enculturation, positions of privilege or disadvantage—to compare, contrast, challenge what is written, said or otherwise believed to be true in connection with the pictures.

Watching a photograph also means asking: what is missing? what is not in the pictures? what is not being shown?

Watching a photograph enables questioning of your own position, your own limits and potentials, the interconnectedness of people on this planet (e.g., with cell technology: exploitation of human labour, destruction of environments, control over information, opportunities for global communication and communities).

The use of cell technology in Rwanda and many parts of Africa is ubiquitous. Urban and rural residents all have access to it; leapfrogging over telephone technology jumping from almost no telecom service to country-wide cell and fibre-optic service. Certainly this is proof of being modern. But technology alone does not eradicate repression, secure basic rights, encourage human flourishing. Watch a photograph, instead of look, glance, accept and dismiss.

Watching a photograph is about engaging, about going beyond the frame, going beneath the surface, about seeking out different perspectives and genuine interest in humanity.

Memory ➔ Witness

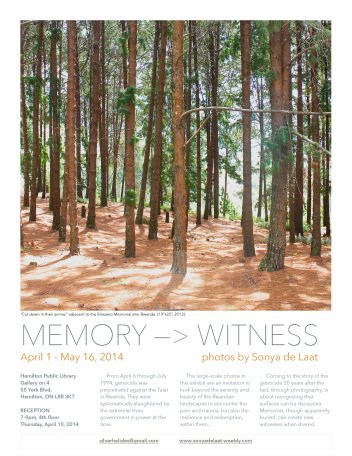

Inspired by a survivor of the Rwandan genocide, this photographic exhibition, displayed from April 1 through May 16, 2014 in the Gallery on 4, Hamilton Public Library, Central Branch, is about trauma, memories in the landscape, and creating distant witnesses. The exhibit engages with the spectator, aesthetics, media, humanity and human rights. Entitled Memories ➔ Witness, the exhibit is an example of a photographic practice that attempts to represent unrepresentable suffering while being sensitive to concerns over exploiting pain. It also invites spectators to become witnesses of a past event that has present impact on lived-realities. A witness can be an eyewitness, but can also be anyone who cares to be affected by stories of violence and continues to share these narratives with others.

These images of Rwandan landscapes are meant to ignite the imagination, to direct the mind away from the path of atrocities, especially ethnic, social, racial, or religious one-sided mass killings. As a way of keeping attuned to empathy and goodwill, the spectators’ minds should be haunted by these images just as survivors are haunted by traumatic memories. The bright hues and large scale of the images in this exhibit, facilitate and enhance imaginative abilities. The titles are quotes told to me by survivors, or selected from published testimonies and eyewitness narratives. They add meaning to an otherwise sublime scene, or act as an intrusive thought - jarring the spectator - giving them a sense of the survivors' experience of memory: it is lived, embodied and can be read in landscapes and material that are otherwise apparently benign or idyllic.

"Mille collines, mille colliques... every hill is a bad memory."

"Running blindly we finally reached the marshes."

"Understand this: the genocide will not fade from our minds. Time will hold on to the memories, it will never spare more than a tiny place for the solace of the soul."

"Cut down in their prime"

"Redemption"

"It's a project that's meticulously planned and properly carried out."

"Mille collines, mille colliques...every hill is a bad memory." In making small-talk banter with a survivor about the aesthetic beauty of the Rwandan landscape, his response to me was that each hill represents sadness and horror. Memories , both good and bad, are in the landscapes. The more we scratch beneath the surface of its beauty, the more we can learn about the human condition and our experiences within it.

"I feel at home here." Under these trees, for nearly the full length of time that this area was defended by genocide resistance fighters, survivors from that group camp here to commemorate the nearly 50,000 people who were killed in this area. Many survivors don't know where the remains of their loved ones are, thus places like this, a mass grave site, become familial places of homecoming and comfort.

"I will always tremble whenever I hear voices raised among the leaves of the banana groves". Running and hiding within the different vegetation in the Rwandan landscape was often the only means of survival. Though this image could just as well be used today for tourist brochures or social/environmental campaigns, for survivors of the Rwandan genocide, this image is a reminder of the animalistic existence they endured to save their lives, and how far they have come since then.

"I'm so afraid of meeting my memories...we breathed deeply of death."

"Running blindly, we finally reached the marshes." For nearly a month, she and about 1000 others hid in the wet papyrus marsh pictured behind her. Only about 50 people survived. Though she lost so many loved ones in that time and in the period of instability following the end of the genocide, she is still a matriarch, community leader, farmer and generous human being.

"Redemption." After having watched the murder of his parents, losing other family members, and spending the remainder of the genocide running and hiding from the Interahamwe, this survivor retuned to school, built a home, started a family, and teaches about the genocide. The home is not a symbol of 'moving on' from the past, but is rather about making the present the best in can be in honour of his family members killed in 1994.